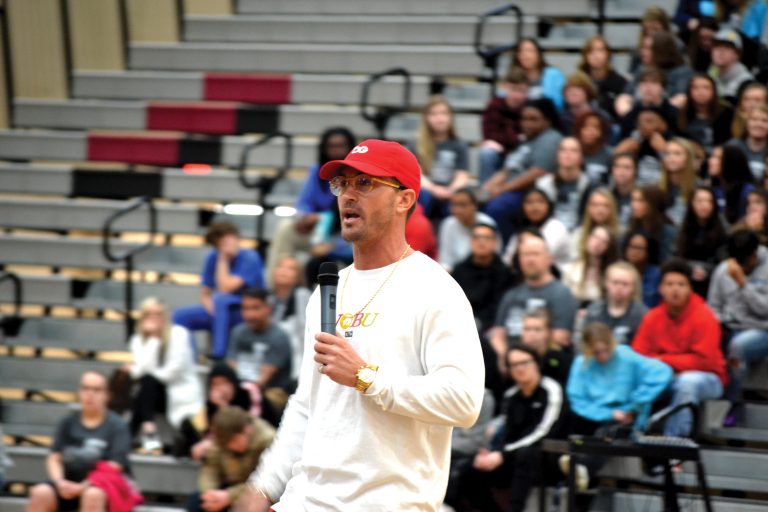

Photo: Pictured above, Tony Hoffman tells his life story to students at Gadsden City High School on March 3.

By Katie Bohannnon, Staff Writer

Gadsden City High School hosted the Substance Abuse Prevention Team of CED Mental Health Center’s 2020 Youth Prevention Conference on March 3, inviting juniors and seniors throughout Etowah County to attend. Through telling their own personal experiences, speakers Nathan Harmon and Tony Hoffman depicted to students how one choice holds the power to change lives, for better or worse.

“I’m not going to stand up here behind a little podium and say don’t do this and don’t do that,” said Harmon. “The truth is, every single one of you in this room, from the front to the back to the left to the right, were born to leave your fingerprints on this generation. You were born to be better, to achieve better, to act better—to be teachers and doctors and athletes and actors. The problem is, a lot of us have to battle the pressure of our community, the pressure of where we come from and the pressure of society.”

Harmon addressed the crippling expectations of community and society and focused on reputations juniors and seniors feel pressured to maintain, resulting in students creating an outer façade to hide their inner emotions. Harmon stated that his own repressive behavior resulted from what he referred to as “moments of impact,” or occurrences in life that affect individuals in a significant and profound manner. Moments of impact occur throughout life, and while these situations are often unexpected, Harmon emphasized that the way students respond to moments of impact is crucial.

Harmon’s first moment of impact arose in middle school when his father called a family meeting in the kitchen. Growing up, Harmon envisioned his family as picture perfect, though that naïve dream shattered when his parents announced their divorce. As Harmon’s world transformed, he began to investigate and ask questions. Harmon soon realized that his parents were not void of flaws; they just hid their problems behind closed doors.

“I learned to do what my parents taught me to do,” said Harmon. “I learned to put on this fake face, this fake smile. I could walk the walk and talk the talk, and on the surface everything looked fine. But behind the mask I was screaming—but I was silent. I didn’t know as a young man that no one is meant to do this alone. I didn’t know as a young man that none of us are meant to be islands, that we need each other. But I wore my mask and [felt] the peer pressure to fit in with groups, the pressure to keep up this image. The problem is pressure begins to build; pressure bursts pipes.”

Impacted by his parents’ divorce and broken family environment, Harmon fought to hold onto an area of his life he felt he could control: his reputation. With an older sister who excelled in high school as a cheerleader and straight A student, Harmon felt pressured to maintain her legacy. As one of the most successful students in his freshman class, Harmon had two best friends who represented the opposite of what he expected from his high school experience. Harmon’s friends were not popular or involved with the cliques he wanted to join, and because of the pressure Harmon felt for his peers to see him a certain way, he walked away from his friends and began to isolate himself.

“Your peer circles matter,” said Harmon. “I don’t need you to tell me who you are. Show me your friends and I can tell you who you are. Some of you have dreams and goals and aspirations, and I believe in them, but the people you’re living life with are negative, critical and compromising themselves and making negative choices. You’ve got another thing coming if you think the people around you aren’t going to affect you.”

Harmon’s isolation resulted in dark days where he struggled with suicidal thoughts and self-harm. When Harmon asked the students listening if they heard a friend, peer or classmate entertaining suicidal thoughts, hands raised throughout the bleachers. Harmon confessed that in each school he visits, he sees clusters of hands raise representing students contemplating ending their own lives. He understands the role mental health plays in the choices students make because he experienced it himself.

Harmon addressed that while some students battle depression, societal pressure manifests in alternate ways for others. He defined “bullying” as verbal, mental and emotional abuse, and recalled the days when he stepped on others who he deemed weaker than himself. Though those abusing others preach a message of carelessness, Harmon stated that broken people hurt other people. Before long, Harmon’s own brokenness and the constant pressure he felt led him to compromise himself.

From his sophomore year in high school until Harmon was 23 years old, he compromised himself with drugs and alcohol, spiraling further and further from the successful young man he once was. Harmon compared drugs and alcohol to a bear cub who appears innocent and harmless. But as Harmon continued to feed and feed his habits, the cute cub transformed into a monstrous addiction.

In July of 2009, Harmon called Priscilla Owens to drive him from a bar to a friend’s home for a party. Amidst the drunkenness and chaos and confusion, the keys left Owens’ hands and Harmon began driving while inebriated. While laughing and joking with Owens who sat in the passenger seat, Harmon became distracted and crashed into a tree at 60 to 63 miles per hour. Owens did not survive the wreck.

Distraught with guilt and grief, Harmon broke down while speaking to Owens’ family, who he felt would loathe him forever. Instead of dwelling on anger and hatred, Owens’ family chose love and forgave Harmon for his mistake. For the rest of his life, they asked him to do two things: do not let their daughter die for nothing and try to make the world a better place.

From that moment onward, Harmon dedicated himself to change. Though he faced a 15 year prison sentence, Harmon began taking control of his life. Through a program that allowed inmates to share their stories, Harmon began speaking at local universities and schools. He became a voice for the voiceless, a man dedicated to helping the helpless and a person determined to invoke positive change and inspire others to make the choices necessary to find happiness and success in life. He presented five habits to the audience that changed his life for the better: transparency, accountability, hard-work, make good choices and value people.

“I wanted the chance to allow people to know that as long as you are breathing, no matter what you’ve been through, no matter what your unique storm is, as long as you’ve got breath in your lungs, you can absolutely take control of your life,” said Harmon. “And the dreams and goals that you have…you can do anything you want. You can leave your fingerprints on history, but you’re going to have to face one person and one person only—you in the mirror.”

In both isolation and confrontation, drugs and alcohol abuse, Harmon displayed how people seek coping mechanisms while rejecting the tool that can support, encourage and guide them towards a better future: community. Harmon invited two students and two educators from the audience to hold a ladder as he climbed it and eventually stood on the highest step, to represent that supportive, encouraging communities strengthen individuals.

“I didn’t use the number one tool that I had—us,” said Harmon. “I had to take off the mask and begin to allow people into my life, friends and mentors, and get to a place where I wasn’t afraid to be honest. We’re better together. Gain the courage to open up. Be honest. Community is how you overcome destructive behavior. Community is where resiliency and perseverance is formed. Position your life to win.”

Speaker Tony Hoffman preceded his message with a piece of advice, encouraging students to listen. Hoffman recalled his predetermined attitude in high school, when he tuned out every school speaker, convincing himself that he or she could never teach him anything. Hoffman urged students to find the similarities between themselves and him, to grasp hold of one thing in his speech that would inspire them to become a better person.

As a child gifted with athletic ability, Hoffman excelled at every sport he played. From basketball to baseball to soccer, Hoffman shined. As Hoffman grew, so did the crowd of onlookers who began noticing his talent. When Hoffman missed two weeks of practice due to illness in the seventh grade, his coach informed him he had to work to regain his spot on the team. But by this age, Hoffman had developed an attitude of entitlement that resented his coach’s requirement that he earn his place.

“Every single person in here needs to understand this, especially your generation,” said Hoffman. “Nobody owes you anything, not even your parents. We’ve got this mentality where people owe us things and we don’t have to work hard like everybody else. I thought because I was the best player on every sports team that people had to show up for me. I didn’t have to do what everybody else had to do, because I was the best. Then I learned that nobody owes me anything.”

While Hoffman walked during sprints in practice and sat the bench the entire seventh-grade basketball season to protest, he simultaneously dealt with emotional turmoil that he did not understand. Because Hoffman’s father never attended his basketball games, Hoffman began to develop a narrative in his mind where his father’s absence meant his father never cared about him or loved him. Hoffman associated his father’s absence with his father’s emotions towards him, but Hoffman never spoke to his father about these feelings—he just buried them inside.

“Every single one of us in this room is going through something,” said Hoffman. “If we don’t talk about the things we’re going through, we get this thing called emotional repression. [Eventually] your emotions overflow. When that happens, you have to find something to change the way you feel to cope with what you’re going through.”

In middle school, Hoffman never realized that his father worked 14 hour days to provide him with the best basketball shoes or soccer cleats, nor did he understand that his father could not get off work because Hoffman’s games were at 2 p.m. He also never realized that the reason he felt so uncomfortable around large crowds of people was because he had social anxiety, a condition his school system never addressed and his family never discussed.

Hoffman’s social anxiety caused him to isolate himself, and that isolation resulted in depression. Hoffman battled depression each morning when he struggled to drag himself out of bed and fought suicidal thoughts each day at school. With so much emotional turmoil, Hoffman began pursuing outlets for his troubled feelings and sought validation from his peers. After developing into a class clown and getting expelled for selling marijuana to a classmate in seventh grade, Hoffman discovered a better alternative and emotional release: bicycle motocross racing.

By the time Hoffman was a senior in high school, he became a top-ranked BMX amateur with several endorsements, featured on the front cover of a major racing magazine. While people expected Hoffman to pursue BMX racing professionally and Hoffman himself knew his bike was the only thing containing his emotions, Hoffman still felt a void in his life.

“I had everything that people thought you could need to be successful,” said Hoffman. “But what [people] didn’t know is this: when I took my helmet off, I wanted to kill myself. People didn’t understand that when I took my helmet off I had all these issues because I didn’t talk about them, I kept them to myself. When I was your age, I thought life was all about the power trip. I thought life was all about making money. I didn’t understand that life is all about being happy and finding the things that you love and the people who care about you the most, and staying around them.”

Following high school, Hoffman abandoned his bike for a job opportunity in San Diego where he expected to earn $120,000 per year. With the combined pressures of a new job that isolated him to a room full of computers and the removal of his emotional outlet, Hoffman began attending parties where he smoked marijuana and drank alcohol to combat his social anxiety. Despite telling himself time and time again that he did not need to smoke or drink, that he was going to become successful, the more Hoffman compromised his standards, the easier it became.

“There is a doorway that exists,” said Hoffman. “I came here to tell you about this door, because you can’t see the door—it’s invisible. When you walk through this door and you step all the way through—drinking, smoking, using drugs—you don’t get to turn around and walk back out when you think you’re done. That’s not the way it works. When you walk through that door, you walk through it to take away something that you don’t want to feel.”

In a short period of time, Hoffman did not linger at the doorway, he walked directly through into a world where his job proved a futile scam and his best friend passed away in a car accident. Confused, heartbroken but unable to properly grieve, Hoffman dove deeper into drugs and alcohol, seeking refuge in the one thing that seemed to fix him: oxycontin.

Hoffman detailed the withdrawals he experienced when he tried to quit using oxycontin, relating the same craving he experienced to the students who vape. He emphasized how the choices students make now will affect their futures and implored them not to believe commonplace lies that try to convince today’s youth that certain drugs are “no big deal.”

In 2004, Hoffman’s oxycontin addiction manifested in a moment that altered the course of his life. Driven to desperation, Hoffman committed a home invasion armed robbery where he stole oxycontin from a friend’s mother. Though Hoffman initially evaded a 10 year prison sentence and participated in a rehabilitation program for 90 days, he could not overcome the addiction that led to the offense and violated his probation, resulting in substantial drug abuse, homelessness and prison.

During Hoffman’s two years in prison, he experienced a spiritual awakening that changed his life. While lying on the top bunk in his cell, he read a quote scribbled in pencil on the ceiling. The quote stated, “Be careful what you think, because your thoughts become your words. Be careful what you say, because your words become your actions. Be careful what you do, because your actions become your habits. Be careful what you make a habit, because your habits become your character, and your character becomes your destiny.”

From that moment forward, Hoffman changed his destiny. He encouraged students to take control of their own destinies, revealing how he changed his life by altering six simple things: the way he walked, the way he talked, the places he went, the friends he had and the things he did. Hoffman made himself available to students, answering their questions and displaying that despite the societal hindrances or limitations students may face, if they make positive decisions and actively choose to better themselves, they are capable of greatness. He encouraged students to be bold, to voice their experiences and to follow what they know is right in their hearts.

“Society and people, including your mom and dad, can only speak to you through their experiences,” said Hoffman. “But sometimes what we’re feeling inside of us is a totally different experience and we have to follow that feeling. That feeling that Noah had even though everyone said he was crazy to build that ark—then it started to rain. That feeling that you have on the inside…that’s how you overcome society.”

Both Harmon and Hoffman represents to students stories of redemption, hope and inspiration. The founder of “Your Life Speaks,” Harmon became the highest booked school speaker in the United States during the 2017-2018 school year, delivering a message of empowerment and perseverance to over 135 high schools and middle schools. As a devoted father and husband, Harmon commits his life to sharing his past so that students might alter their futures, speaking hope to nearly 750,000 people on one platform or another.

Like Harmon, Hoffman dedicated himself to a greater purpose and walked through a new door into a life free of addiction. As a former BMX Elite Professional and 2016 World Championship Masters Pro class second-place winner, Hoffman transformed himself from athlete to coach, guiding Women’s Elite Professional Brooke Crain to a fourth-place finish at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games in Brazil. The founder of the non-profit mentor organization The Freewheel Project, Hoffman travels 200 days a year, speaking to audiences in schools and on the TEDx stage alike.

Harmon and Hoffman prove to students that one choice does not hold the power to destroy their lives—if they empower themselves to change for the better. Through community and communication, individuals can express their experiences and develop reliable support systems who encourage, uplift and embolden them to pursue their dreams and achieve their goals. Despite the limitations of society, the pressures of culture and environments, Harmon and Hoffman inspire students to realize their worth, to understand the seriousness of their decisions and to discover their purpose in life.

“Good choices will always position you in life,” said Harmon. “Feed what you want to grow; starve what you want to die. It doesn’t matter if people don’t believe in you. It’s not their dream—it’s yours. Go get it.”